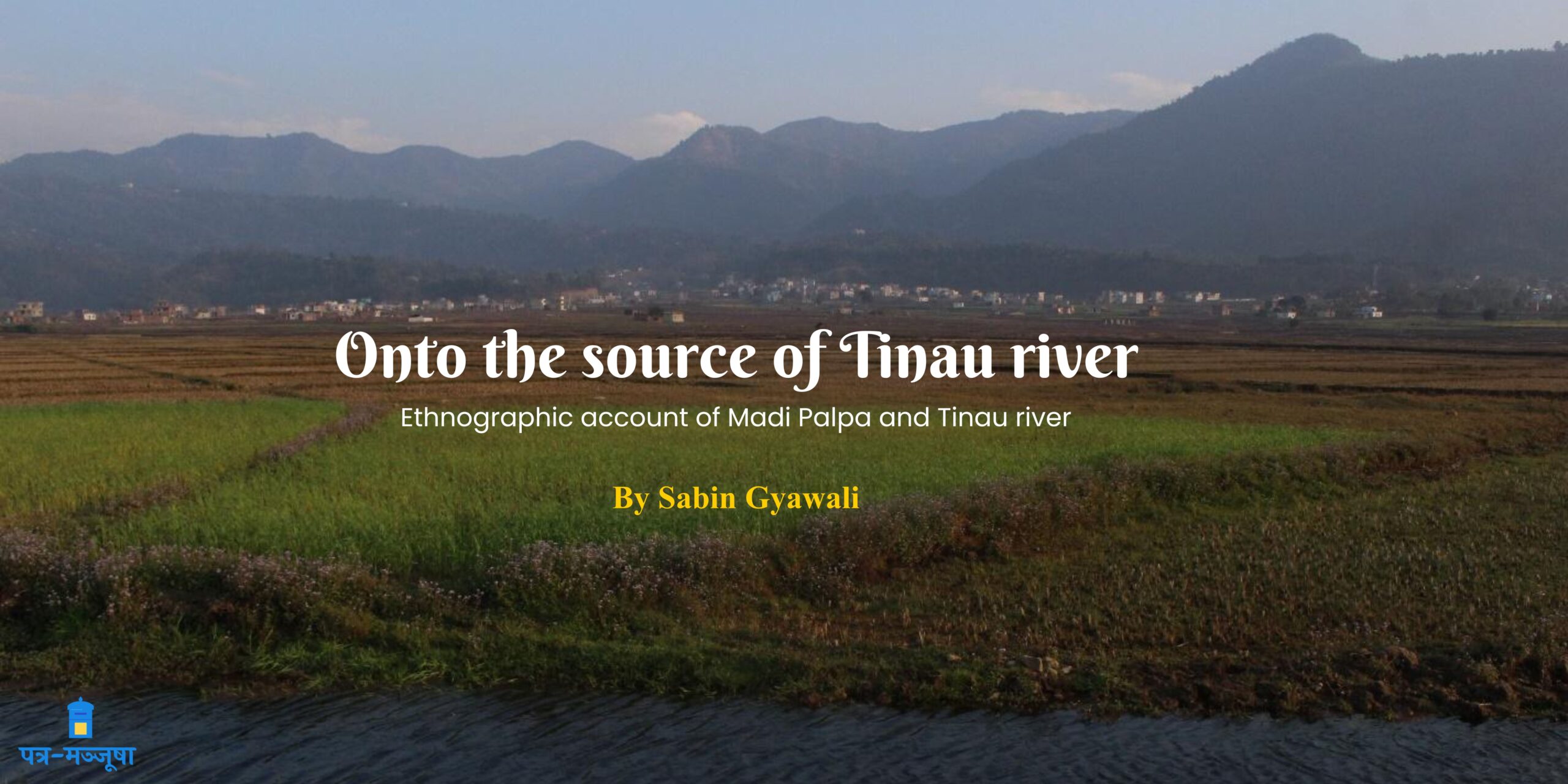

People in Palpa Nepal, live with the proverbial wisdom of things. When one in use seems insignificant, they use another one. “Wherever you turn its flow, the canal and the conversation take their shape”/ “कुरो र कुलो, जता मोडे पनि बग्छ”. It was a desire to walk onto the source of Tinau river, Palpa, from Madi phaant (माडी फाँट) to Lemdhem (लेमधेम), alongside the places it inhabits. The idea bore its seed when I trekked to a glacier lake, Kahphuche (क्हफुचे), to find that it is the source of Madi river (मादी खोला) which flowed by my maternal house in Lamjung, Bhorletar. It felt like a new epistemology. Walking onto the source of a river felt like walking through to find an understanding of source, so profound that it became a new methodology to navigate my own feelings. A new perspective emerged. As barely as I am able to change my point-of-view, I could surely embody a different one. Stepping foot into the water or walking alongside it, felt like I was able to see people and places around, keeping the river as my point-of-view. People of different ethnicities, socio-economic backgrounds, birds, plants, ecosystems of sand and stones, all tagged along the river; interpretations and values attached to the river too.

Beginning

The journey in mental retrospection starts from me and my friends sitting down by the bank of main canal of Sohra-Chhattis Mauja Irrigation System Canal (SCMIS) at Madhauliya, Tilottama Municipality. Open landscape of wheat fields in late January of 2023 A.D. and a small tree of guava made a place where we preferred to settle down and have our daily dose of “Dwelling” (Heidegger, 1993)), which we said in Nepali poet Devkota style to be a spot for “विचरण/thinking in a space”.

The knowledge came to us over there that in the dry season of January, almost all river water was diverted to SCMIS canal at Kanyadhunga and Ittabhond and flowed throught whole of southwestern Rupandehi district, dividing into multiple sub-canals, relatively differential in size (Yoder, 1994). Thus, implying the importance of Tinau river for agriculture and cold breeze, for people to settle down in summer heat. Dwelling north from the point of Dwelling we passed through the changing landscape of SCMIS canal, where it opened up in most of the part in Tilottama Municipality and closed in Butwal Sub Metropolis, ending up at Tinau river in the northernmost part of Rupandehi district administrative territory at Kanyadhunga, Pulchowk.

Tinau and its etymology

‘षट्शताब्दीत एवात्र विक्रमाब्दागम :व्कचिद् ।

बुद्धवल्ली बुढवली बुटौली बुटवल् क्रमात् ।।

तिलोत्तमा-तपोभूमी-मूला या सा तिलोत्तमा ।

तिनाव-पदवी प्राप्ता नदी बुटवलीबहा ।।

पालपादेवरालीस्थो नेपालकलसम्भव: ।

विद्वान मीनप्रसादोSयमं सप्तमास्तिकदर्शनन् ।।४९।।‘

Yogi Narharinath has written in his 2038 B.S. publication that the name came to be Tinau from Tilottama, changed with time to be Tilaaw and subsequently Tinau (Shrestha, 2076). The name Tilottama comes from an Apsara in Hindu mythology where ‘Tila’ is the Sanskrit word for sesame seed or a bit and “uttama” means higher. Tilottama, with reference to Mahabharata is described to have been created by the Vishwakarma, at Brahma’s request, by taking the best quality of everything, therefore meaning, who is composed of the finest quality (Municipality, 2024).

Nirmal Shrestha writes in his book पाल्पा नुवाकोट: the living heritage that Tinau river originates at Madi Area (माडी क्षेत्र) and at Charchare (चरचरे), Chaubise Mile Triveni (Twenty-four Mile Triveni), becomes a confluence with Tanseneli river (तानसेनेली खोला) which on its own has mixed with Dumre river (डुम्रे खोला) before coming to the confluence. He further adds that before coming to Charchare, Tinau river joins with Sisne river (सिस्ने खोला) and Bahrabise river (बाह्रबिसे खोला) (Shrestha, 2076) at a place called Ghorbanda, Mathagadhi Rural Municipality, Palpa. And south from Charchare, accommodates Dobhan river (दोभान खोला) at Dobhan and Jhumsa river (झुम्सा खोला) at Jhumsa before coming to the plains of Terai at Rupandehi district (Shrestha, 2076). On our journey, in addition to Nirmal’s writing, we found other two water bodies, that comes into Tinau; Rakaule Dhaap river (रकौले ढाप खोला) and Khahare river (खहरे होला). Later in June 21 of 2024, travelling by Madi area alone in late-afternoon I stopped by Badwari bridge (वदवारी पूल), which translates as the bridge in near end of the dam, continuing the custom of Dwelling. I saw that tinau river had no water in it, and I realized it to be a seasonal river, different to the glacier rivers like Madi river which get the running water whole year. Southern down the Madi area, at the newly constructed Tinau Bridge at Amlyan, Tinau Municipality, the river got its water from Rakaule Dhaap river, which is a wetland, big enough to provide water throughout the year, as a buffer water valve in deep monsoon by not letting Tinau river flow towards paddy field when it comes charging in monsoon and in dry season by providing water to a riverscape dry and full of soil. Khahare river too was seen with water, coming down to Tinau confluence, near Badwari bridge. Tanseneli river flowed down with its share of water, relatively with a generous amount at Charchare, making it a very important tributary to Tinau river as a whole in the late June, before monsoon has arrived here.

“Rice from cold water is tasty”

In January 2023 when me and my friends stayed at Madi for half a month the preconceived notion that Tinau is used for irrigation of Madi area changed completely. While as per ward chairman, Tansen Municipality Ward No. 09, it stayed true that using the Tinau water at Amlyan, they have been doing wet agriculture harvest thrice a year, it coincided with the wet nature of land near Rakaule Dhaap. as it was also said that local people plant Anadi variety of paddy near wetlands (Rakaule Dhaap and other) because it needs more water than other. And also, it’s true that locals have constructed a new irrigation canal on early May of 2022 called Garnya kulo (गर्न्या कुलो), named after Grahan (ग्रहण)/new moon night, the day when they offered goats and started the canal; from Tinau river at Badwari bridge with budget of 4 crore (40 milion Nepalese Rupee). On July 21, 2024 the monsoon was yet to arrive for paddy plantation and paddy seed beds were only in vision. It wasn’t a surprise as Tinau river had no water, but some fields were seen with paddy plantation amidst dry land, using water of several wetlands and water sources that’s been there for decades. In the late winter of January, walking into the riverscape, touching water and taking off the slippers came like a generic sensation. Then I found water not only in the river itself, but in the fields and grounds that either take water from it or give to it. Amidst the ongoing project to lift water from one of the other, smaller Dhaap to Pokharathok, on one early morning of January, after it had rained all night, a web of spider in a knee-high bush was seen with water trapped everywhere around it.

I had to stop by there for another session of Dwelling, remembering Heidegger now in memory when I sit down to write it. The image of the wet-spider-web came to me like an inner landscape of Madi area, which has many wetlands and water sources. For fresh and cold drinking water, locals use it. “Rice from cold water is tasty”/ “चिसो पानिको भात मिठो हुन्छ”; locals have sense of it. Not only in the taste difference of old varieties of Jarneli, Anadi, Gaurrya, Hangse Mansara, Fulpaato to new Mansuli hybrids; also, within the same variety in cold and warm water irrigation. While the ward 09, Tansen municipality, is concerned with undesirability of letting irrigation water from one field drop down to the other, making water warmer in the subsequent field and rice less tasty, ward chairman addresses the absence of proper irrigation canal system in Madi area. To its complacency, many water sources have been functioning for cold water irrigation in relatively lesser land around the Madi, at a significant distance from Tinau river. Presence of several wetlands and division of Madi area in many wards and between Mathagadhi rural municipality, Tinau municipality has made it difficult to conceptualize as one single agricultural land for management; said the administrative officer at Krishi Gyan Kendra, Tansen.

In addition to this, the agricultural productivity and history of the land is one that’s huge and laborious. “Never give ox and you daughter in Madi”/”माडीमा गोरु र छोरी कहिल्यै नदिनु”. People living there recall the huge workload they used to have when they did regular agriculture, which nowadays is different as high yielding rice varieties have come to use, giving twice or thrice the previous yield and also as newer generation has migrated to cities like Butwal, Pokhara and Kathmandu and do not seek for rice from home with compulsion/need.

River ecosystem; Tinau

A recent geological survey at Rakaule Dhaap found that the depth of wetland as deep as 50 meters; “if you are drawn in dhaap, you will reach Butwal” (ढापमा गाड्यो भने, बुटवल पुर्याउछ), which the ward chairman relates with formation of Madi area itself. In addition to it, around three decades ago Tinau river came huge at the place called Laalpaati (लालपाटि) and stopped the flow of a small river that came from hills, northwest near Laalpaati and created another wetland in the area. My father said that we used to have paddy fields over there and since Tinau did what it did, the field stayed covered with water. The flowing of Tinau river through such a wide plane landscape conditions itself in a very phenomenological way to be the river it has been. The huge wetland is not the reason for Tinau to be the river it is, neither for the other wetland to be formed as a reason of river, but is a situational condition for the Dasein of river and wetlands, as a river ecosystem. The recently elected local ward government which has the Rakaule Dhaap within its territory is desiring a plan to build a lake like water reservoir at Rakaule Dhaap to maintain the water constancy in the river and control its local encroachment. The google earth pro images of the Rakaule Dhaap two decades back shows landscape change.

Soil for Stone; Stone for Soil

The change in landscape of river in Madi area coincided with the low torrential flow of water and its putrid smell. On one same day 12 kilometer walk in late January from Madi area, south to Charchare, passing by the hilly gorge of river, we wanted to swim in the river which looked tempting in its freshness and torrential flow. Stones were all over the river as it flowed down the gorge and imprints of water level were seen in stones.

There was no definite bank, as water flowed through the stones leaving no only-sand in its edges. While in Madi area, the absence of stones now in the river was said as a reason for Tinau river to fill its depth with sand and rise high into the landscape. A local said to me that three to four decades back, there used to be stones in the river and added; “ढुंगाको साहारा माटो, माटोको साहारा ढुंगा” (Soil for stone, stone for soil). There’s a saying that stones find their base in soil and soil hold onto stones for not letting themselves flow away. There used to be a lot of stones in the Tinau river at Madi area. After stones were taken, the soil lost its ground. Without stones, river fills itself with soil and lose its bank, and at monsoon, brings all the soil to the nearby paddy fields.

History, Myth and Indigeneity

Ecological landscape brought cultural landscape in curiosity. Who were the people that lived first here? What makes an indigenous population? Is Indigeneity the word of current time? Is the ability of people to inhabit the land when on one could? Many questions prevail and no clear answer was found. Ward 09 Chairman said that the Hindu Aryans might be the first to come and settle in the hills. While many claim that hill Tharus; namely the Kumaals are the indigenous people. Kumaal that we met in Laalpaati said that their grandfathers came from Pokhara and many Kumaals came from different part of Nepal and settled down there. It is evident in their houses being clustered into 4-5 houses per family, while others like Gairey of caste group are clustered in 30 around houses of same lineage. While Kumaals were considered inferior by high caste Brahmins, Kumaals too didn’t eat food touched by higher castes. While they worked in the field of higher castes as agricultural laborers, they prepared their own food. Befitting the Ward Chairman’s saying, the name “Madi” came to be from Hindu Rishi, Mandabya (gotra: of Gyawali surname) and Madi in particular is a place near Amlyan/Damkada, Tinau Municipality. And whole place was named after its name. Mandabya Rishi myth in Mahabharata is about how some thieves after stealing king’s wealth, left some in his ashram while running away and later King accused him of being a theif (Hindu, 2016). While the localized version of the king is “ghore kings” and Madi is the ashram place of Mandabya Rishi. King hung the Rishi for several days but owe to his supernatural spiritual power, he didn’t die and later he was released, but Rishi cursed the king and myth still remains that “Those who eat the rice of Madi, shall never have their intellect rise”/ “माडीको भात खाएको मान्छेको बुद्धि कैलै न-आवोस्” and also “Gyawalis who stay in Madi will not get goodness”/ “माडी बस्ने ज्ञवालीहरुलाई फलिफाप हुन्न”. My father said that grandmother took him to nearby Shivaratri festival celebration in Parbas, Palpa and fed the grain offering from that place, rather than own’s rice from Madi, in his rice-feeding ceremony (after 9 months of being born). And it was ubiquitous in people farming/living in Madi to use rice from another place in rice-feeding ceremony, and it is dissipated among everyone in Madi; the Magars, Kumaals and caste groups. While also its important to know that with time and now people say that they are anyway cultivating the hybrid varieties from cities; they have not taken the custom with rigidity and associated no heavy norm with compliance. The myth of curse also goes as “Cursed by Sati”/ “सतीले शरापेको”, referring to myths around Satyawati bajyai (सत्यवती बज्यै), a local female deity, evident with a lake name Satyawati Lake in Palpa district. Myths around Satyawati are prevalent too. A local female resident had Satyawati bajyai in her dreams saying the deity won’t take her too far, but with her in Purin dhaap (पुरिन ढाप), because bajai felt bajai was alone there, and three days later the body of the woman was found there. Purin dhaap is associated with being a branch of Satyawati bajyai and the woman who had the deity in her dreams had come there in dhaap from Tansen to dig it and “earn very much money”/”टन्न पैसा कमाउन भनेर” , but died there.

In search of old cultures associated with land, if that is to mark the indigeneity, we roamed around but to no avail in a month-long period of time. Mandabya Rishi, Satyawati Bajai marked the history of place with caste group. But if we are to consider the capacity of people to survive in a land for a crucial period of time and be its guardian and its user, Kumaal’s indigeneity comes with their ability to live there in the times of Malaria, while everyone beside them couldn’t. Or, it could be said that Kumaal, belonging to Tharu community in their Pan-Identity sense, came to Madi with their ability to live with malaria. It gave them the possessive and legal authority, both, of the land at Madi, to cultivate it for themselves and for other owners who lived in the higher nearby hills of Palpa. In the present day powerplay of indigeneity, Madi area still finds none of its own and seems not concerned in finding one as currently for any need.

In the absence of culture that came down from then older generations to older generation of now, cultural revival has been a new thing on move. An old grandmother recently got to know that the name of the river was Tilottama and not Tinau and it was as holy as the Ganga River, Gandaki River; from a religious educator who she found online. With all conviction she said that the source of the river is powerful and also, she goes to bath in the river in auspicious days like Ekadashi, Purnima and Aunshi. She added that now she feels it important to know these religious historical statuses.

Source of Tinau: Lemdhem

People of Madi rarely knew about the source of Tinau. Most obvious answers being places called Humin/Tahu/Lemdhem. Very few knew that it was Lemdhem and also been there. Grandmother who recently knew the old name of Tinau was once of them. We inquired further and help from people and google map went to the place northeast from Madi area, called Lemdhem, Purbakhola rural municipality 4, Palpa. The name of Tinau river was not Tinau up there in Lemdhem, neither was Tilottama. People considered the original source to be a kholsi/(खोल्सी), a small river (which has its source again a bit uphill from there at Kaaulepaani), and said it becomes river as it goes down; and another source called dharadi(धारादी). And the local Magar name of the previous one, kholsi, being, bharam/bhurung river (भरम्/भुरुङ खोला). What do they mean by bharam/bhurung? They said bhoramm means the water that remains after filtering the local beer jaand(जाँड). And because it looked hazy and also the kholsi looked hazy, they named it so. On the day of Maghesankranti, Magars there offer Pinda(पिण्ड), to their ancestors, do Naag puja, Prakriti (nature) puja where they turn towards the Satyawati lake towards a faraway hill, south-east from there. It’s unknown what can be considered the origin of Tinau river. The two sources that people of Lemdhem consider to be the origin, originates from their own land. They neglect one other water body from another hill across in another region, which seems like is also a source of it as it falls down quite near to where bharam river reaches a lower hilly gorge. It reminds me of a relative in Madi who mentioned with mischievous laughter that they wanted to establish the narrative that Ashram of Mandabya was in Pokharathok, Bagnaskali rural municipality, but failed. The social status game to it felt resembling in these two occasions. Some said, it is called Tinau because it has three taps. Some said, it is called tinau because it comes from three sources. Some said, it is called Tinau because three rivers mix into it. While, trying to make sense of people talking in metalogues it seemed at once that I heard people saying it is called Tinau because it originates from the place called Tinau. Well, I myself bear a potentiality to create another interpretation.

Upper Lemdhem faces the scarcity of drinking and irrigating water while Upper Lemdhem has recently got water taps enough in their community. Upper Lemdhem is an upland area to any of two sources; bharam and dharadi, while Lower Lemdhem lies just in place to use their water. It was said back in Madi by Ward no.9 Chairman too that, because they have used water up in the source for household purpose, tinau gets lesser and lesser water. Also, people in Lemdhem said that after the road construction started, the water in the sources decreased. While uphill in Lemdhem, it’s a matter of relief and still the upper Lemdhem is yet to get the benefit of easy drinking water, downhill in the Madi, it’s a concern for someone.

Conclusion

It started from huge open land of wheat farm and SCMIS canal and ended up in Kaaulepani, at Lemdhem, A journey of walking through changing landscape, from plains to gorges to Madi Phaant to a small source uphill. The absence of age-old traditions associated with hills, land and river, suggest the migratory and late inhabitation of area around Tinau river, north from Charchare. While the mythical mutualism in Madi would suggest the agricultural dominancy in lifestyle. People from many different parts of western Nepal inhabit the Madi area, who did agriculture and based their life and understanding upon the land then and what prevailed on the land later on, building and associating already available myths with new incidents. And also, in the absence of a rigid cultural custom of age of tradition, and influence of modernization and nearby market in Tansen and Butwal, the cultural change also seems evident. The epistemological methodology in the beginning makes it able to put the history of Tinau river in its name Tilottama, an aged grandmother who recently subscribes to the idea and the meaning behind the name of river in Lemdhem. It’s as if the filtered beer water flows downhill and a hindu woman baths in it for its historical and religious value and everyone everywhere, using it for irrigation. Different people from different communities live by the river. Experience as such can give us a framework to see river as a universal water thing, rather than any religious governance as things that connect people to their river are treating it as a water body, drinking swimming, fishing, dwelling, utilitarian measure for food and ecology, knowledge about the drying and monsooning of river and participation activity like building irrigation canal from river. The study of power and politics in the people and place around Tinau can be done in classical Marxian/Neo-Marxian way by finding and locating marginalized, poor and discriminated people, understanding them with Bourdieu’s sense of different forms of capital.

Bibliography

Heidegger, M. (1993). Building, Dwelling, Thinking. In M. Heidegger, Basic Writing (pp. 361-362). London: Routledge.

Hindu, T. (2016, June 24). Sage Mandavya’s story. Sage Mandavya’s story. India: thehindu.

Municipality, T. (2024, June 28). Tilottama Municipality. Retrieved from http://tilottama-rupendehi.blogspot.com/p/tilottama-municipality.html

Shrestha, N. (2076). पाल्पा नुवाकोट: the living heritage. Butwal, Rupandehi: Nuwakot Bikash Samiti.

Yoder, R. (1994). Organization and Management by Farmers in the Chhattis Mauja Irrigation System, Nepal . Colombo: International Irrigation Management Institute (IIMI).